The answer to climate change lies in technology and engineering

Plan A has failed — there is no effective global deal to manage the risks of climate change. So what is Plan B?

Twenty years of conferences, reports, intergovernmental meetings, public debate and most important mounting evidence of the early effects of climate change have failed to control or seriously mitigate the risks. It is time to go back to the Paris climate change agreement and think again.

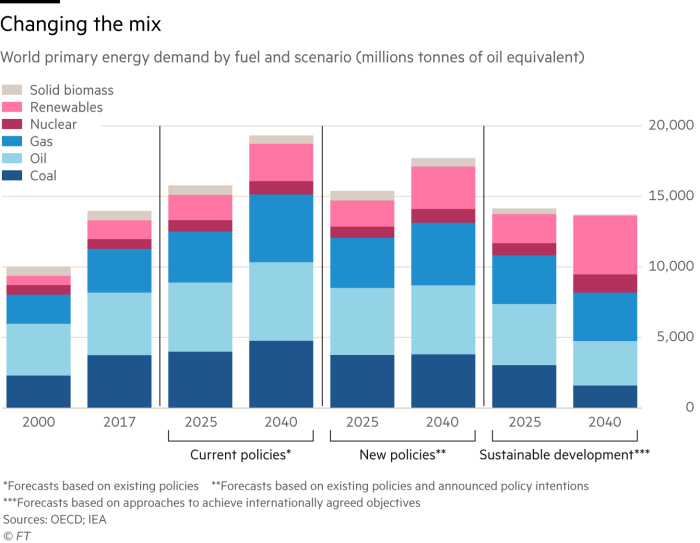

The reality is simple and undisputed — hydrocarbons continue to supply about 80 per cent of global energy needs each day, just as they did 10 or 20 years ago. The only difference is that the absolute amounts behind this percentage have grown. As a result the amount of carbon emitted continues to rise — CO2 emissions are more than 40 per cent higher than they were in 2000, according to figures produced by the International Energy Agency.

A host of reports over the past few weeks have confirmed that judgment — including the IEA’s World Energy Outlook, the US government’s National Climate Assessment and the most recent study produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

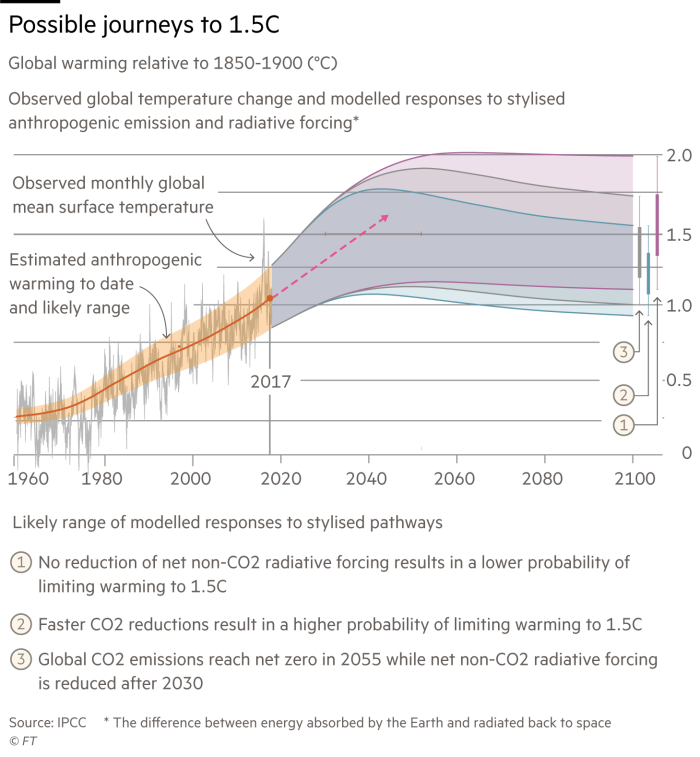

The situation is serious and getting worse. There is no world government and nationalism is the strongest political force of our times — and so there is no viable collaborative mechanism for tackling global problems. We are on an inexorable track to the point at which atmospheric carbon concentrations exceed the levels judged likely to raise temperatures by 1.5C.

Is there an alternative to passively accepting this as an unfortunate inevitability?

Historically, political co-operation has not been the source of all or even most of the answers to the world’s great challenges. Medical science rather than politics has largely eradicated polio or other diseases. Nor did politics produce the technologies that led to the “green revolution” in agricultural productivity which has made food available to more of the world’s 7.2bn citizens.

The answer to climate change will come, if it comes at all, from science, technology and engineering. That should be the subject of the discussion now — it should be scientists rather than politicians who regularly gather to formulate solutions to the challenge.

The first question for them to address is how to focus the numerous efforts being made. Everyone has a favourite priority and the world’s scientific academies should organise the debate and make the choices.

Lord Rees, former president of the UK’s Royal Society, a scientific academy, has suggested four practical strategies to countering climate change in his most recent book, On the Future. They are: improved electricity storage; increased low-carbon power generation; greater efficiency of consumption; and more reduction of emissions from methane, black carbon and CFCs — all of which would contribute to mitigating global warming.

The overall aim, put simply, should be to identify, create and disseminate technologies that can give everyone the chance to use low-cost, low-carbon energy as soon as possible.

The purpose of any event to mark progress on the ambitions expressed in the Paris agreement should be to confirm such choices, to share knowledge on the work being done in different parts of the world and to identify the areas where more effort and resources are needed.

If some states decline to participate, too bad. A coalition of the willing is better than no coalition at all. The exercise should not repeat the mistakes of the political debate over the past 20 years by always waiting for the slowest to catch up.

The next question is how the science should be funded. The best answer is to pool resources. Why not establish an investment fund open to subscriptions from both the public and the private sector?

The technologies that meet the challenge are likely to do well, and those who have invested deserve a reward. If some people make money through the development of products that serve the common good, good luck to them.

If additional funds are needed, why not offer individuals and companies a tax deduction of 110 per cent against income for investments in such a fund?

No one can predict the results of scientific work, but it is surely better to do something more instead of simply ploughing on with a strategy which has failed. The UN-backed Conference of the Parties should start by accepting that reality.

Exhortation and attempts to change public policy, however well intentioned, have changed too little. As the clock ticks and the risks grow, it is time to try a different tack.