Surge in solar and wind power marks shift to low-carbon energy

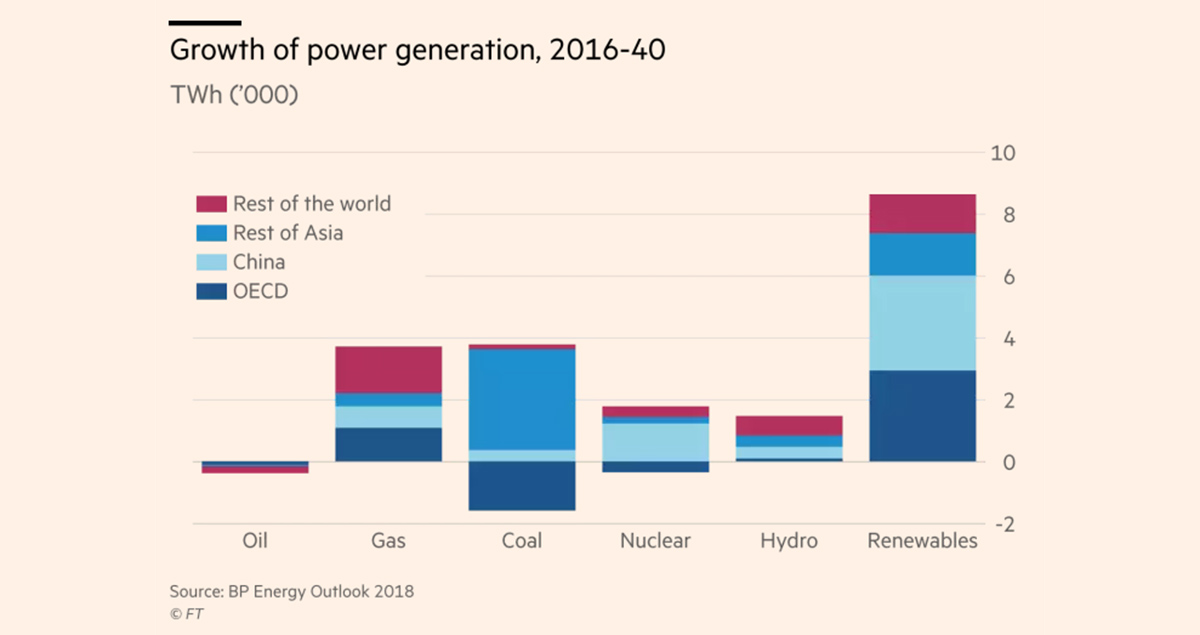

When BP’s economists published their annual review of world energy this week, the survey revealed a surprising statistic: 17 per cent of the world’s energy growth last year came from renewable sources, the largest increase on record. New installations of renewable energy were equivalent to the energy output of 69m tonnes of oil — about as much energy as Sweden and Denmark consume in a year.

This development might have been unthinkable a decade ago, when wind and solar power were much more expensive than they are today. However, a surge of investment in renewable energy sources over the past decade combined with falling costs for new energy technologies has brought about a profound transformation in global energy production.

Part of the reason for this massive shift was the Paris climate agreement, signed in 2015, when more than 170 countries agreed to reduce their emissions to limit global warming to below 2C.

“If you look at the world, you see that there is actually more collaboration about climate change than there is about many other issues that are confronting us,” says Christiana Figueres, the UN’s leading climate change diplomat from 2010 to 2016.

There are still challenges — including the fact that the US, originally a signatory to the agreement, has said it plans to withdraw from the deal. By 2020, the signatories of the Paris climate agreement will have to agree on legally binding limits for their carbon emissions, as well as come up with financing for developing countries to pay for the cost of making the transition, which has been a sticking point in the past. “Addressing climate change is not easy or we would have done it,” says Ms Figueres. But she adds: “It is not insurmountable. It is absolutely complex — it is realistically complex.

The exact scale of the problem will be made clear this year, when a panel of scientists will release a report on the impact of 1.5C of global warming — and what level of emissions cuts would be necessary to limit global warming to that level. Early drafts of that report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s leading authority on climate, have suggested, based on current trends, that the 1.5C threshold will be breached before 2050.

With that report in hand, delegates to the annual UN climate talks in December will have to consider what measures can be taken to reduce emissions much more radically than in the past.

Much of the progress in curbing carbon emissions in the past five years has come from the growth of wind and solar power, which have experienced dramatic price reductions.

“People thought offshore wind couldn’t be cost effective 10 years ago,” says Matthew Wright, managing director in the UK for Orsted, the Danish energy company that operates 10 offshore wind farms in the UK.

Improvements in turbine technology have caused prices to fall by half in the past three years, he adds. “Now it is at a point where it is truly competitive with other forms of power generation.”

Meanwhile in solar energy, panel prices have also been falling. The International Energy Agency estimates that solar will soon be the cheapest source of new electricity in some countries. As prices come down, policymakers are moving away from subsidies for wind and solar and shifting toward auction-based systems to reward the lowest-cost producers of renewable electricity.

The fall in subsidies has added a degree of volatility to the wind and solar sectors. One of the biggest surprises was the decision by China this month to cut support for new solar installations — a policy change that will reduce demand this year in the world’s biggest market for solar panels.

After years of rapid growth, global demand for solar panels is expected to be lower this year than it was in 2017, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), which revised its estimates after the Chinese move, which sent the share prices of panel makers plummeting.

Global investment in clean energy has risen over the past decade and hit a high of $179bn in 2015, according to BNEF, but it has remained below that level in the years since, primarily because of the falling investment in Europe and the Americas. Investment in clean energy this year is likely to feel a dampening effect from China’s solar crackdown, and from the slowdown in wind installations in Europe.

After levelling off between 2014 and 2016, global carbon emissions ticked up again last year, partly because of increasing energy consumption in China.

Despite this, Ms Figueres remains upbeat. “The long-term trend is toward decarbonisation,” she says. “We have had ups and downs, and we will continue to have ups and downs.”