Opening Hell’s Gate: Japan’s geothermal expertise in Kenya

Native Americans used it to cook food; ancient Romans used it to heat spaces. In some places it’s so readily available that even the snow monkeys of Jigokudani have learnt to use it to bathe in and relax. Geothermal energy is one of the most accessible energy sources on our planet.

Sites where geothermal can be commercially exploited are potentially very valuable to the countries that house them. They provide a virtually unlimited supply of constant, sustainable and cheap energy — a tempting prospect for nations seeking to reduce both emissions and energy costs, while increasing energy security and capacity at the same time.

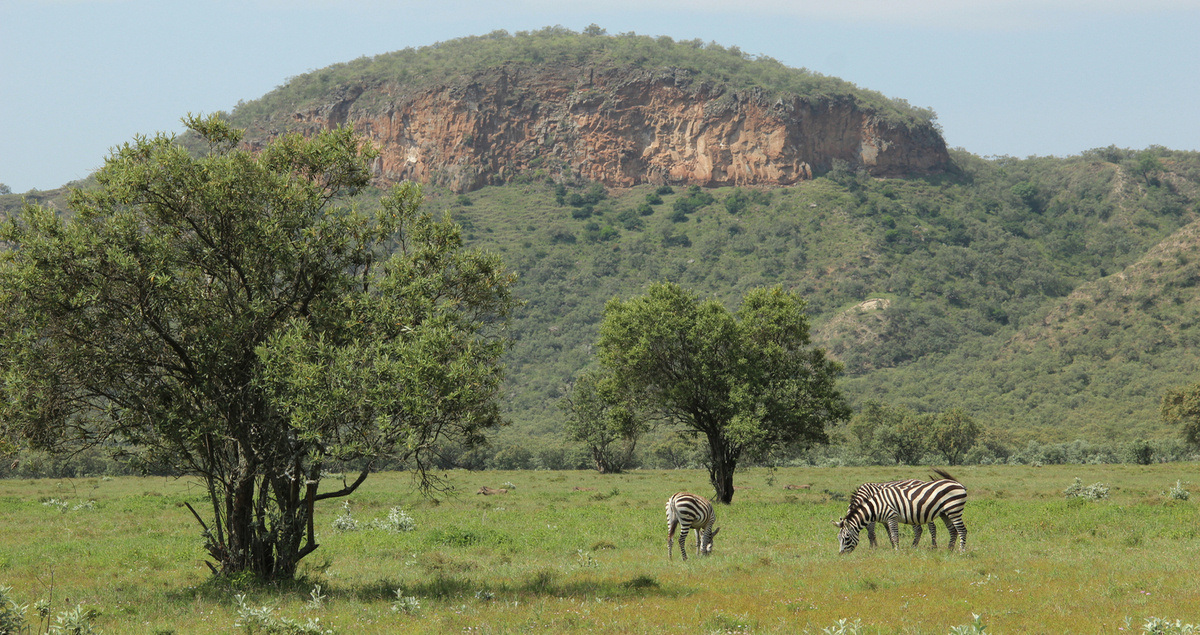

Hell’s Gate National Park in Kenya is one of those places.

The latent renewable energy escaping from the ground in Hell’s Gate was always there for the taking. But commercializing it took a blend of government will, United Nations and Japanese investment, scaled-up technologies and proper operations management to create a viable and long-lasting geothermal energy stream.

How Kenya opened up Hell’s Gate

The name of Hell’s Gate National Park — which is around 100km northwest of Kenya’s capital city Nairobi — reflects the intense and dramatic geothermal activity within its boundaries. This is as a result of its position on the East African Rift System, which traverses the region from the Red Sea to Mozambique.

Today, thanks to areas like Hell’s Gate, Kenya is already one of the global leaders in geothermal capacity and is committed to expanding its geothermal potential even further. By 2040, around half of the country’s total energy requirements will come from geothermal power in the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) STEPS scenario — an achievable aim given the amount of geothermal potential Kenya has available to it.

Of course, extracting energy from the Earth’s subsoil for commercial use is a more technically challenging task than simply finding natural hot springs to relax in. And it comes with high capital expenditure costs and high risk, which have been barriers to entry in the past.

So how did Kenya overcome the hurdles to become a top-10 nation in geothermal capacity?

Research, investment, technology, support

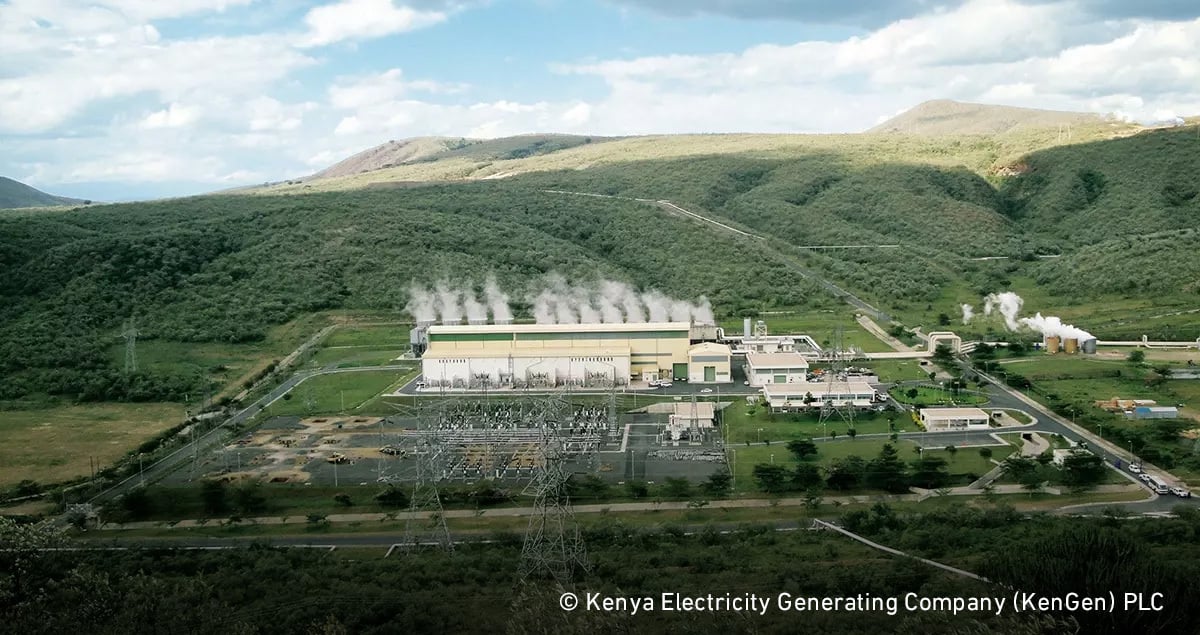

Geothermal research and development in Kenya began in the early 1950s, with the first drilling operation — which was unsuccessful — following in 1956. In 1972, with the help of investment from the United Nations Development Programme, research accelerated, facilitating Kenya’s first geothermal power plant. The Olkaria began operations in the 1980s with a 15 MW geothermal power generation plant.

But capacity increases in the subsequent years were slow, until the government set up a state-owned development company in 2008 to accelerate geothermal resources in Kenya. This helped reduce upfront investment risk, opening the country up to further foreign investment. Since then, capacity in Kenya has grown much faster.

Japan’s geothermal role in emerging markets

Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) Group was there in Hell’s Gate from the beginning, delivering the first steam turbines to Olkaria power plant back in 1981 — and it is still supplying the power plant over 40 years later. The most recent MHI Group’s units were completed in 2019, adding 165 MW to the total capacity.

Japan itself is also a big investor in geothermal around the world. The country’s development assistance agency Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) says it has financed 17% of the world’s geothermal capacity since 1977, all for projects in Africa, Asia and Latin America. JICA works as a bridge between Japan and emerging countries, providing loans, grants and technical assistance to help these nations unlock their geothermal potential.

The combination of opening up global investment potential — coupled with a long-term engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) partner — provided the capital, expertise and equipment required to take advantage of geothermal energy. Projects like the one in Kenya’s Hell’s Gate could prove to be a successful model for other countries to adopt.

Mitsubishi Power, a power solutions brand of MHI, is already working across the world to become an EPC partner and provide equipment for geothermal activities. It has orders for 112 units of geothermal power generation across 13 countries, including Indonesia and the Philippines.

Meanwhile, MHI Group company, Turboden, is also providing binary power generation systems globally, including for the Palayan Geothermal Power Plant in the Philippines.

“In Kenya and beyond, geothermal development in East Africa needs more than just the construction of power plants,” MHI geothermal expert Yu Morita says. “It also requires excellent operation and maintenance technologies, which Japan can provide. We will continue to contribute to the development of Africa and further assist in their efforts to curb global warming.”

Geothermal needed across the globe

Figures from the International Energy Agency (IEA) show that geothermal power is currently substantially short of the target in its net zero emissions by 2050 Scenario, and that global power generation capacity must jump substantially in the run up to 2030.

“Despite geothermal energy’s great resource potential, growth is hampered by a lack of policies to address pre-development and resource exploration risks, with anticipated expansion of less than 6 GW over 2022-2027 concentrated in Africa and Southeast Asia,” the IEA warns.

Furthermore, the agency highlights the need for innovative mechanisms to support more geothermal projects in emerging countries, mainly in the form of funding through multilateral or bilateral development banks, such as the JICA.

Initiatives like those from JICA and MHI Group — which provide the investment, technical support and machinery to create and maintain geothermal energy systems — could well provide a successful strategy for other countries with geothermal capacity potential and emissions targets.