Big Oil harnesses power of data analysis to ensure survival

Eni’s Sannazzaro oil refinery, 60km south-west of Milan, is an industrial island surrounded by agriculture. But as well as the jumble of pipes, furnaces and storage tanks that characterise such sites, there is a less familiar scene.

Rising from a football pitch-sized parcel of land on the edge of the refinery are six futuristic buildings — grey, rectangular and windowless — without any obvious association to the production of petroleum and diesel taking place nearby.

These buildings are home to one of the world’s most powerful computers with capacity of 18.6 petaflops, a measure of computing speed. That is three times quicker than Facebook’s fastest and twice that of Nasa’s, according to the Top 500 global ranking of supercomputers.

Eni’s investment in computing shows how Big Oil is counting on Big Data to keep it competitive in a changing energy market. After decades of dominance, conventional oil and gas producers are under pressure from surging US shale supplies as well as the long-term shift towards renewable power and electric vehicles.

Alessandro Puliti, head of development, operations and technology at Eni, says technology will be crucial to keeping costs down and productivity up. Ever more powerful data analysis will allow new oil and gasfields to be developed faster and with less risk, he says, and make them more productive once on stream.

Eni’s supercomputer can run 100,000 high-resolution reservoir simulations — 3D models of oil and gasfields — in 15 hours, compared to the hours it takes a reservoir engineer to run a single simulation using old software. This accelerates the design work needed before development begins and allows fewer, more productive wells to be drilled.

“A great part of cost control is the ability to control uncertainty,” says Mr Puliti. “The supercomputer allows us to take earlier decisions, with less risk.”

Examples include Eni’s Zohr gasfield off Egypt, which was brought on stream last December in less than two-and-a-half-years from discovery, a record for a deepwater project. The powerful software has similar benefits in optimising the operation of existing fields, as well as downstream facilities, such as pipelines and refineries. Uses range from managing reservoir pressure to maximise oil and gas flows, to utilising artificial intelligence to predict the need for maintenance work.

“If you can avoid drilling a well or avoid a maintenance shutdown, you have already made a huge return on your investment in the technology,” says Mr Puliti. Other oil and gas groups are making similar investments. Total agreed a deal with Google in April to jointly develop artificial intelligence for data analysis in exploration and production. The French group also announced the trial of a robot to take over some manual tasks on its Alwyn platform in the North Sea. The 1m tall, 90kg stair-climbing robot, called the Argonaut, is designed to carry out inspections such as measuring temperatures and detecting gas leaks.

BP, meanwhile, is using drones and “crawler” robots to look for microscopic cracks inside a hydrocracker at its Cherry Point refinery in the US. Previously, it took a team of engineers 23 man hours to inspect the unit. Now, says BP, the same work can be done in one hour, reducing time needed for costly maintenance shutdowns.

Lydia Rainforth, analyst at Barclays, says that “use of digital technologies to improve productivity is set to transform the big oil companies over the coming decade”.

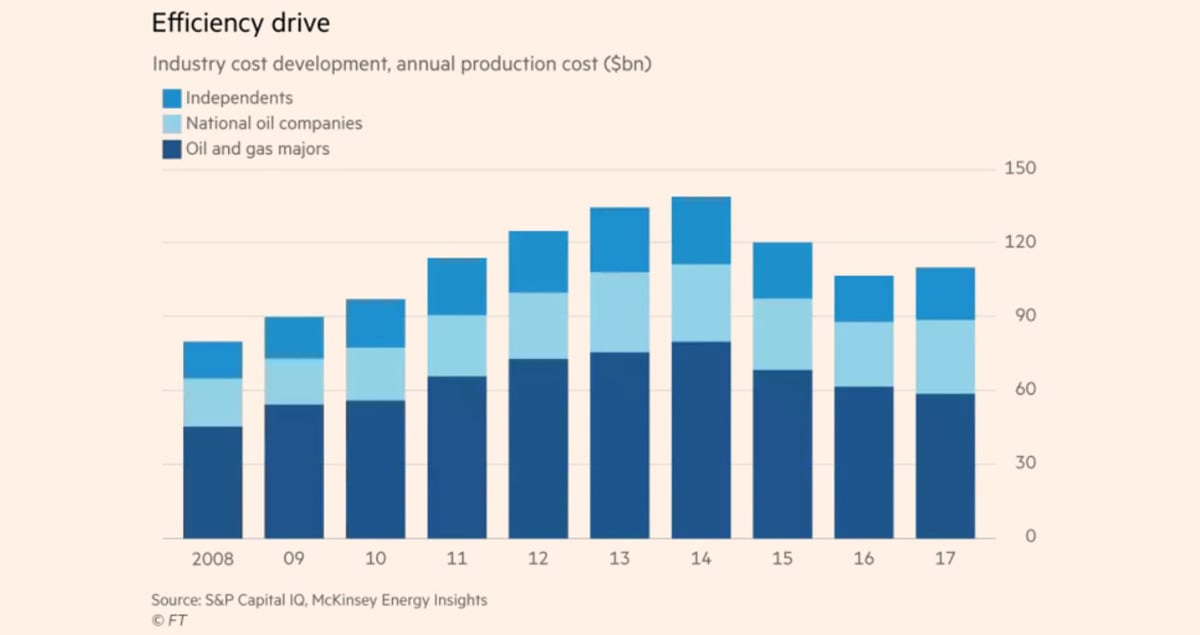

High labour costs and low returns on capital have made oil companies a poor investment relative to other sectors, making an efficiency drive long overdue. Productivity levels in the oil industry — measured by output from labour and capital — are 30 per cent to 40 per cent lower than the economy-wide average for the OECD group of wealthy nations, according to Barclays.

“This is simply not sustainable and it is clear to us that a new way of working is required,” says Ms Rainforth, who estimates the value of the potential productivity gains for European oil and gas majors at an annual $60bn.

Increased automation should help keep headcount down as the industry recovers from a long downturn but Mr Puliti insists that technology is about raising the productivity of existing workers rather than replacing humans altogether.

“There is increased employee satisfaction because people are able to do higher quality work,” he says. “Performance levels are higher than they were in the past.”

Greater efficiency will help improve shareholder returns but, increasingly, it looks like a prerequisite for oil companies’ survival in a world of plentiful shale resources and increasingly low-cost renewable energy.

Bernard Looney, head of upstream exploration and production at BP, says the industry must shake off its reputation for wasteful spending and learn from leaner sectors like carmaking which improve productivity year after year.

“We’ve moved from scarcity of resources to abundance,” says Mr Looney. “It’s going to be incredibly competitive. We’re going to have to demonstrate productivity improvements on an ongoing basis — and technology and data will be key to that.”